On my way to the Xu Guangqi Memorial Park I passed a modern statue of him just around the corner from the Park’s entrance. Erected in 1994 this sculpture commemorates a man born in Shanghai during the Ming Dynasty in 1562, when Mary I was on the throne in England. It was a time in Chinese history when the study of mathematics had gone into decline. He became Minister of Rites and Grand Secretary to the Ming Court, eventually being called The Minister. The son of a farmer who had his own vegetable farm in Shanghai he nonetheless had an education from the age of six, getting a bachelor’s degree at 18, but only obtaining his Jinshi degree -passing the three-yearly court exam – in his thirties.

Although he himself was very clever, it was his liaison with the Italian Jesuit, Matteo Ricci, that was the real making of the man. Together they translated several Chinese Confucian texts into Latin and, more crucially, several important Western texts into Chinese, the most useful being Euclid’s Elements which includes number theory which introduced the concept of rational and irrational numbers, the theory of proofs leading to solutions such as Pythagorus’s theorem, and geometric

algebra which is able for example to find the square root of a number and solid geometry which gives for example the volume of a cone. Xu Guangqi also introduced ideas of astronomy, agriculture and military science to the Chinese.

Passing the stone at the entrance to his memorial park you go over a small typically Chinese bridge and through a

memorial archway, where you are confronted with a path – the traditional sacred road of the Ming Dynasty, lined with various statues of human officials, horses, tigers and sheep leading to a stark white cross. It was  under Ricci’s influence that Xu Guangxi converted to Catholicism in 1603, taking the baptismal name of Paul Siu. His descendants have been Catholics ever since. Beyond the cross is his tomb, where his remains were eventually buried eight years after his death.

under Ricci’s influence that Xu Guangxi converted to Catholicism in 1603, taking the baptismal name of Paul Siu. His descendants have been Catholics ever since. Beyond the cross is his tomb, where his remains were eventually buried eight years after his death.

The tomb consists of ten vaults and is shared with the remains of his wife and his four grandsons and their spouses. The park is beautifully serene and at this time of year, parts are deeply shaded. The tomb itself is in a clearing of trees, so the cross and tomb are highlighted by the sun, as is a Japanese maple that stands in another clearing close by. There are statues of Xu Guangqi depicting his achievements

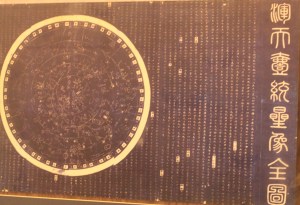

throughout the park together with various Stele. This one, discusses the fact that Xu Guangqi led the reform of the Chinese calendar in 1629 based on the work of Kepler and his astronomical observations, leading to the completion of the Chongzhen Calendar in 1632. The statue of the gun

depicts his introduction to China of the concept of a “Rich Country and Strong Army” in his book Cook Xu’s Words about military techniques and strategies he gathered from his western friends. He was criticised for daring, as a mere scholar, to discuss such matters, even though he was worried about his country’s inability to defend itself against the northern Manchus. It was a concept adopted by Japan in the 19th Century

under the name Fukoku kyōhei, much to China’s detriment. He was also interested in improving agriculture, fertilizers, stemming famine and improving irrigation systems and wrote an enormous work of over 700,000 Chinese characters, left in draft form at his death but complete by others and published in 1639.

As in all Chinese parks, there was much

everyday activity, from an old woman slapping her thighs (I’m not sure what this achieves, but I have seen it often), to games of cards, or inactivity sitting by the fish pond or the drained water lily pond.

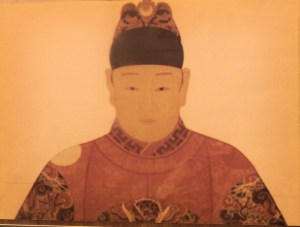

But there is more to this lovely serene park than all this. In its south east corner is the Xu Guangqi Memorial Hall. It is built in the typical layout of a Chinese home – in a quadrangle formation with one stone-linteled entrance. And through this entrance you can see a head and shoulders statue of Xu Guangqi framed by the door’s stone surround. He wears the hat of a Han Chinese official of

But there is more to this lovely serene park than all this. In its south east corner is the Xu Guangqi Memorial Hall. It is built in the typical layout of a Chinese home – in a quadrangle formation with one stone-linteled entrance. And through this entrance you can see a head and shoulders statue of Xu Guangqi framed by the door’s stone surround. He wears the hat of a Han Chinese official of

the Ming Dynasty which consisted of a black hat with two wing-like flaps of thin, oval-shaped boards called the wushamao. Around the walls of the quadrangle are a series of stele, and inside the rooms surrounding the courtyard is a small museum about the man’s life.

the Ming Dynasty which consisted of a black hat with two wing-like flaps of thin, oval-shaped boards called the wushamao. Around the walls of the quadrangle are a series of stele, and inside the rooms surrounding the courtyard is a small museum about the man’s life.

Xu Guangqi devoted his life to various aspects of the natural sciences, learning from the westerners that he met and applying what he learned to books on agriculture, astronomy, mathematics, water conservancy, measurement and the calendar. As a child he lived in the Old City of Shanghai and received his early education at Longhua. As he worked his way up through the successive imperial examinations he worked as a private tutor to support himself. When he took the Imperial Examination in Beijing in 1597 the chief examiner, Jiao Hong, recommended that he should be the no.1 candidate from all of China, known as a Jinshi, which thus lead to a role in the Ming Court administration.

Before his death Xu Guangqi produced in draft form The Complete Works of Agriculture, a seminal work on agricultural methods, irrigation etc. based on scientific concepts.

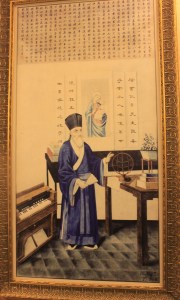

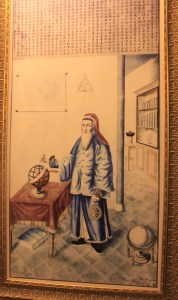

There were three other men important in the story and legacy of Xu Guangqi. They are depicted in these copies of four early 20th Century watercolours painted by the Tusan wan Gallery in Shanghai (the one of Xu above, the others below). The originals now hang in the Ricci Institute for Chinese-Western cultural history at the University of San Fransisco.

Matteo Ricci had come to China to preach in 1583 and studied Chinese and over the years he adapted to Chinese customs. He did this so well that he became known as “Western Confucian Scholar”.

He introduced modern western natural science to China whilst also acting as a conduit for ideas of Chinese culture to permeate to the West.

The Italian Matteo Ricci met Xu in Nanjing for the first time in 1600 and by 1607 the two of them had finished the translation of the six volumes of Euclid’s Elements. Here Euclid made an overall systematic summary of the ancient Greek mathematics and served as the earliest model of of the deductive system in maths based on axioms (i.e. based on an initial premise).

It was this Jesuit missionary who introduced Xu to the idea of a calendar based on the movement of the earth around the sun. Xu Guangqi jointly translated The Introduction to Astronomy with him, producing first set of western scientific books in Chinese. Xu was introduced to the idea of a global world (rather than the then Chinese view that it was square one) and the concept of latitude and longitude and the geometry

required to forecast the movement of the earth, sun, planets and stars in space. Matteo Ricci produced the first modern world map for China, showing the coastlines of the five continents on a spherical world with an equator and lines of latitude and longitude.

Emperor Chong Zhen (enthroned in 1627) allowed Xu GuangQi to revise the calendar in line with astronomical observations after he and his students predicted the solar eclipse of 1629 and thus he freed the Chinese calendar from its previous emphasis on auspicious days and other superstitions. The calendar, the Chong Zhen almanac was completed after his death. It consisted of 137 volumes and included much of the earlier work on the movement of celestial bodies.

Xu put forward his theory of “a rich country and a powerful army” and wrote about the training and management of soldiers and wrote a five volume book Cook Xu’s Words in retaliation for those who mocked that a scholar could not possibly know about military matters. In it he wrote of military management and strategy.

Xu argued that the military needed artillery, and it played an important part in protecting the Ming Dynasty such as protecting the Liaodong peninsula in Southwestern Manchuria.

Johann Adam Schall von Bell, a German, came to China in 1622. By 1630 he was summoned to Beijing to be in charge of the Calendar bureau, manufacturing astronomical instruments such as reflecting telescopes and editing the Chong Zhen Almanac.

Ferdinand Verbiest was a Belgian missionary who set off for China in 1659. He continued the work of Xu Guangqi and the other Jesuit missionaries before him. By 1669 he was working at the Qing Court editing books and compiling calendars. Between 1680 and 1681 he founded 320 artilleries.

This part of Shanghai is called Xujiahui. It means the Xu’s family gathering here and is thus named because Xu’s Catholic descendants settled around the tomb and built farms nearby. Jingyi Hall was the first Catholic Church in China paid for by the fourth generation granddaughter of Xu Guangqi. After the opium wars, when China again opened up to the West, the Christian missionaries chose this area for

their headquarters, as it was already populated with native Catholics. The missionaries built a Christian cathedral, a convent, a school, the Siccawei observatory, the Siccawei Library and a museum in an area just north of Xu’s tomb. It thus rapidly developed into the largest centre of Western culture in modern China.

Thank you for the description and photos. I was told I am the 17th generation, I live in Kuala Lumpur now. My siblings are in LA & Melbourne. My grandaunty (father side) lives in shanghai she is 90plus and still going strong.

LikeLike